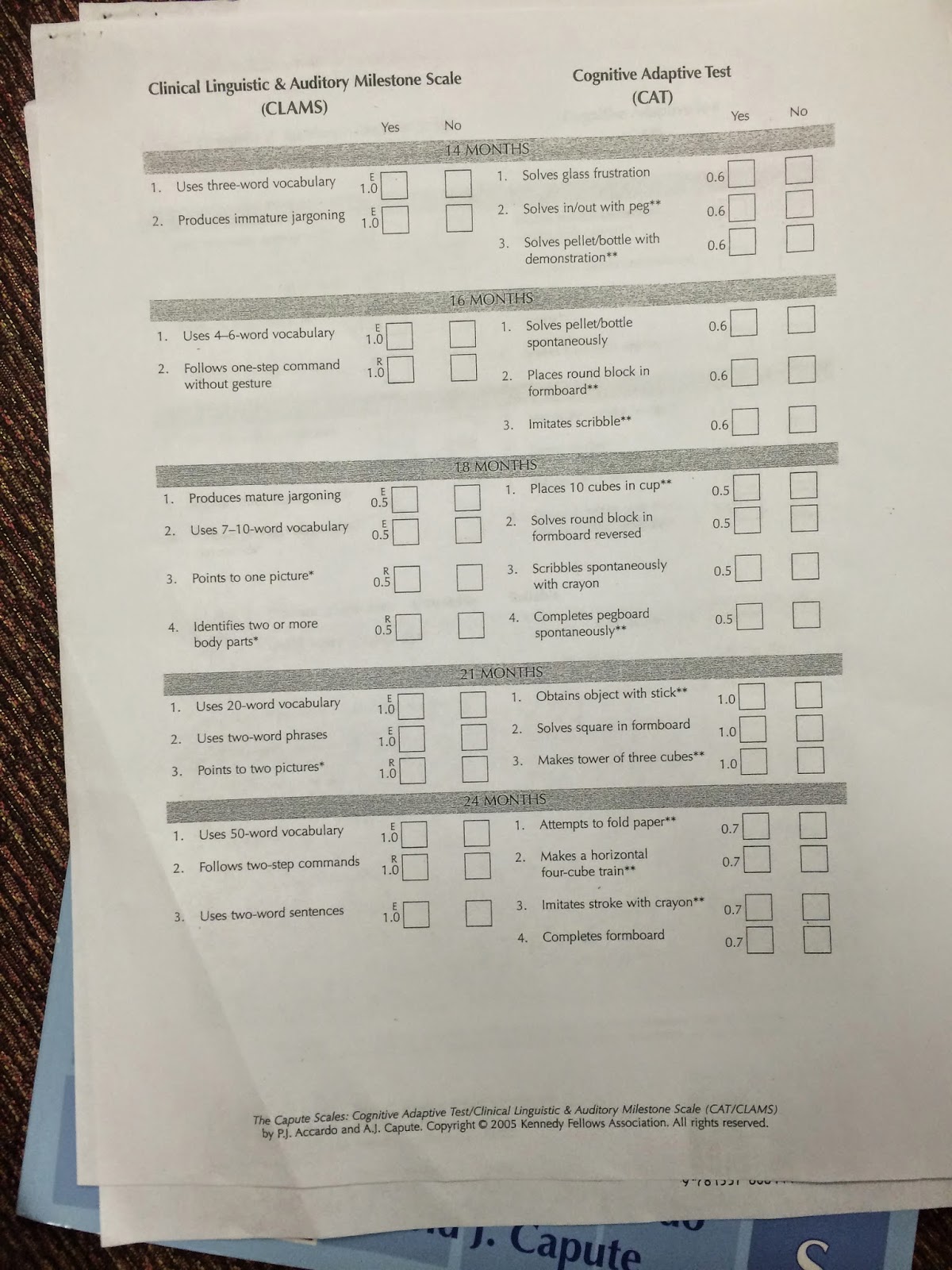

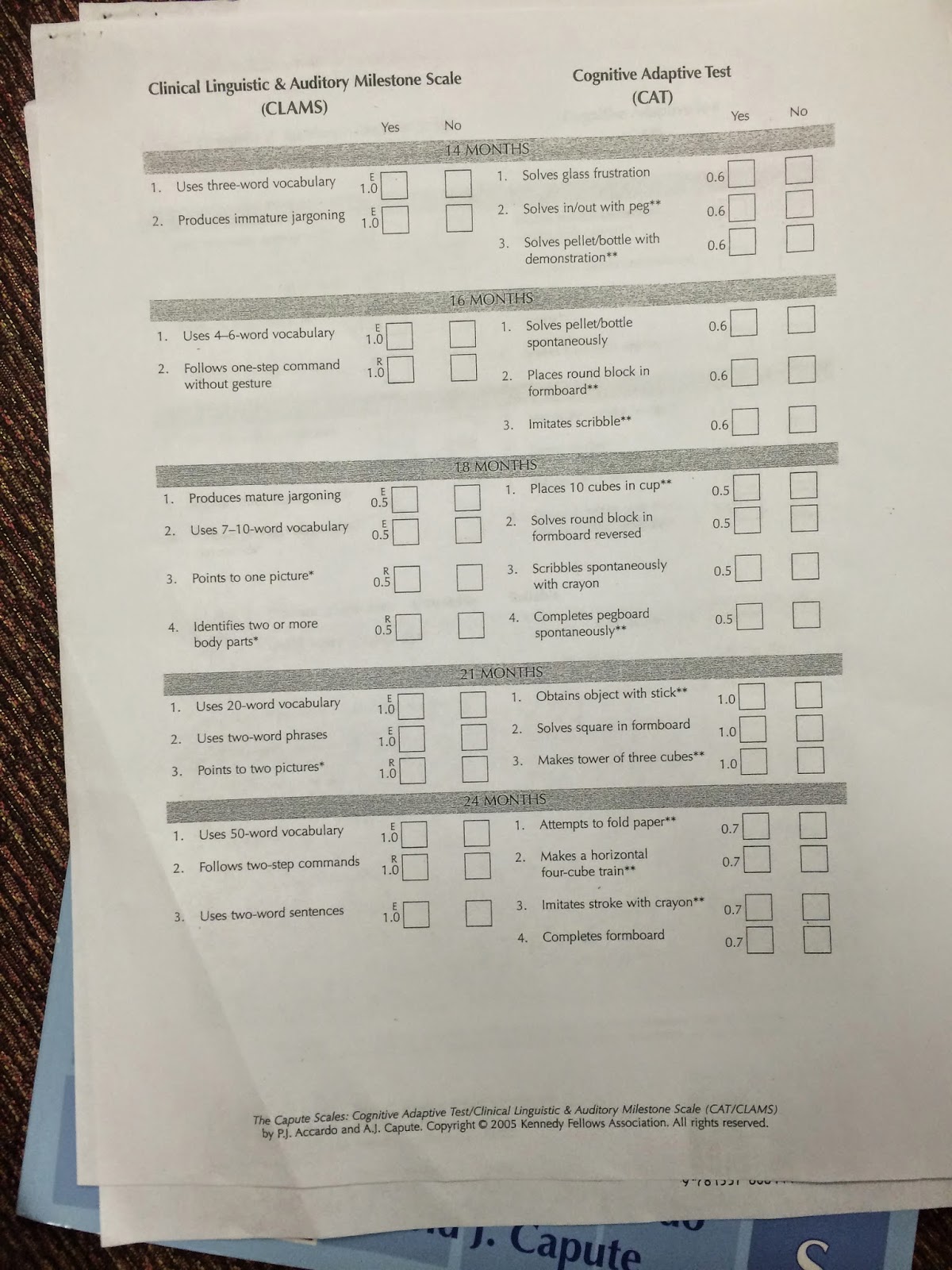

Week Six at Mount Sinai has likely been my favorite week at Mount Sinai thus far. During this week, I learned how to administer the CAT/CLAMS (the Clinical Adaptive Test/Clinical Linguistic and Auditory Milestones Scales) to former NICU patients. The purpose of administering this test to this population is to quantify the cognitive, linguistic, and visual-motor skills in children who were born pre-maturely. In doing so, the developmental pediatrician can understand whether the child's development is age-appropriate. If not, she can subsequently recommend additional therapies (occupational, speech, physical, etc.) to enhance and develop skills that might be missing.

To administer the test, I sit with the child at a miniature table and set of chairs, while the developmental pediatrician sits at her desk. We do not typically like parents to accompany us in the testing room because clinical research has found that child responses are heavily influenced by parental presence and therefore their responses are not valid representations of their true skills. Once the child is seated, we like to bring out some toys and let the child play and become comfortable with us and the testing environment, since most of the children that we administer this test to are under three years of age. When we begin, we clear the table to eliminate any potential distractions and let the child focus on the object or toy that we present to them. We follow a worksheet, which lists specific tasks that are appropriate for different ages. According to the manual, it is best to start testing skills a couple months below their age to allow the the child the opportunity to "show off." Doing so, not only boosts their self-esteem but probably makes them more engaged in the tasks. We look at their performance on these age-selected skills and then determine whether we move "forward" and advance to test older skills or move "backwards" and test younger skills. A threshold dictates our decision to move forward or backwards. For example, if we test a eighteen-month-old child, we expect this child to be able to do eighteen-month-old milestones, which includes spontaneously scribbling when given a crayon and a piece of paper. However, if the child needs someone to show them how to scribble or cannot scribble at all, we move backwards down to the set of skills for sixteen-month-old children. If they successfully complete enough tasks at the eighteen-month-old level, we move on the to twenty-one-month-old level. But the key to administering this assessment is letting the child dictate the pace. As the administrator, you must read the child's body language and understand when you should give the child time to figure the task out on their own or when to intervene and show them a task. You also must speak at their level and find different ways to say the same prompt over and over to help them better understand what you are asking them to do.

I was thrilled to have the opportunity to administer this assessment this week. The child I tested was a two years old and incredibly shy. We brought her into the testing room and she stared at the floor. She made no eye contact with me or the developmental pediatrician and completely ignored the toys we gave her to play with. After about fifteen minutes of silence, we brought her mother into the room and she warmed up. She was a very bright young girl who showed to be advanced cognitively but slightly delayed linguistically. From this assessment, the pediatrician recommended speech therapy. I look forward to my opportunities to continue to administer this developmental assessment to NICU follow-up patients over the next three weeks!

|

| CAT/CLAMS Page 1 |

|

| CAT/CLAMS Page 2 |

|

| CAT/CLAMS Page 3 |

|

| CAT/CLAMS Page 4 |

No comments:

Post a Comment